In October 2017, the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), with funding from the Swedish Government, announced that they would support 10 industry doctoral students from companies within the national food system. I was lucky enough to be invited by NBR to be the doctoral student in their ultimately successful application. For more information on this call and the process we went through with it, see my post ‘Living LivsID‘.

This is a brief description of the project’s structure, as it was at its completion.

Title: Long-term post-harvest field storage of sugar beet

Introduction paper*: Long-term Storage of Sugar Beet and the Role of Temperature – a review. SLU publications | Researchgate

Paper 1: Impact factors on the tissue strength, damage susceptibility and storability of sugar beet. Lead from IfZ Göttingen, in collaboration with NBR Nordic Beet Research, Stichting IRS Netherlands, and IRBAB-KBIVB Belgium. Results summary | Presentation of results at IIRB2020 | Paper online (behind paywall).

Paper 2: Method for the In-Season Texture Analysis of Sugar Beet Using a Handheld Penetrometer. In collaboration with NBR Nordic Beet Research, Stichting IRS Netherlands, IRBAB-KBIVB Belgium, and IfZ Göttingen Germany. Results summary | Full paper online | Paper on ResearchGate | Presentation of results at IIRB2020 | Poster on ResearchGate.

Paper 3: Using ventilation during storage for the drying and cleaning of sugar beets. I’ve written a longer post about this.

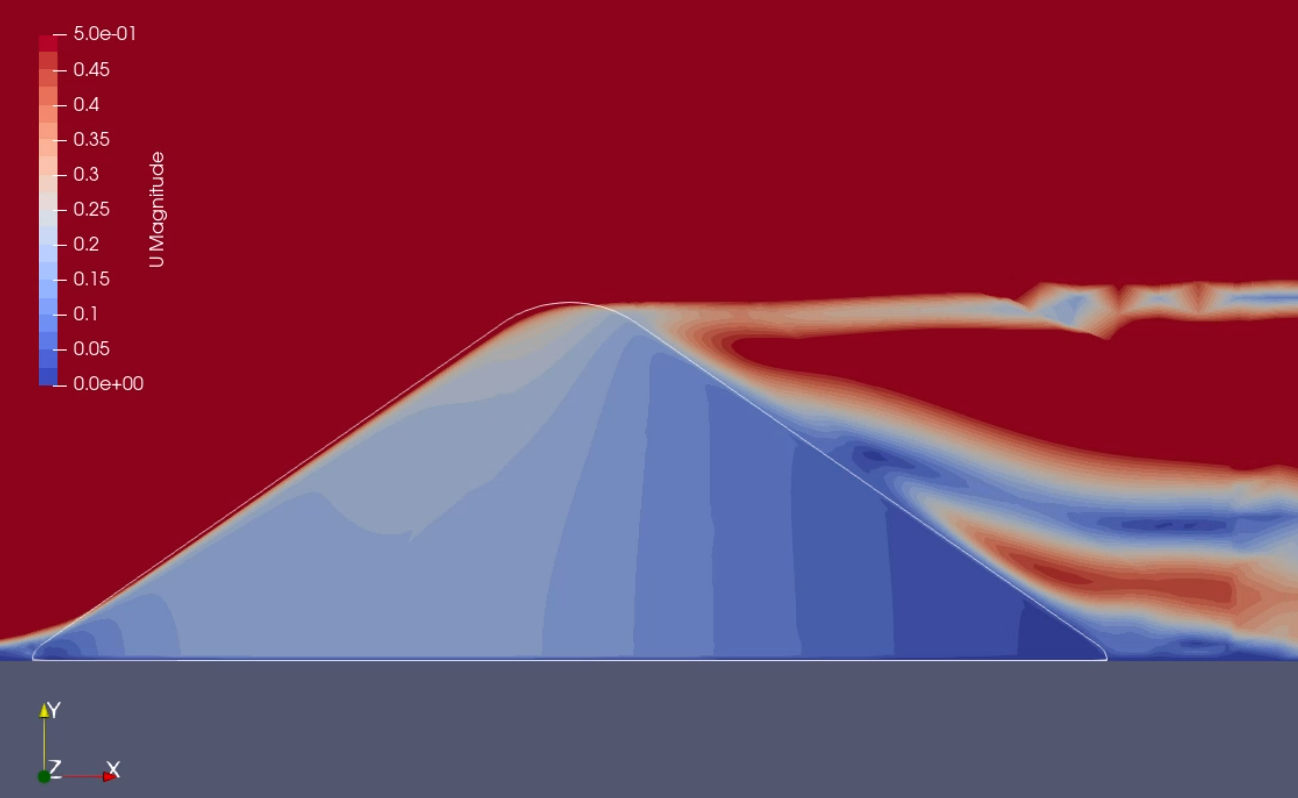

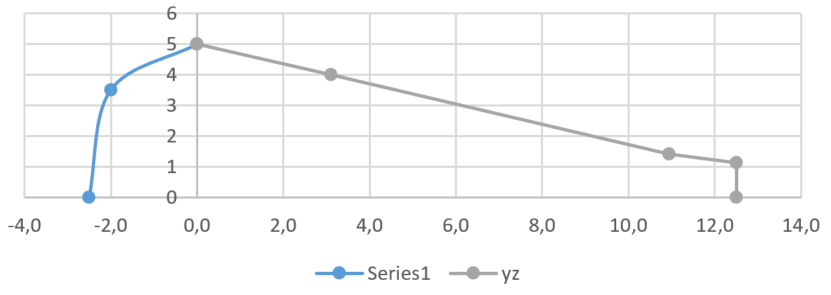

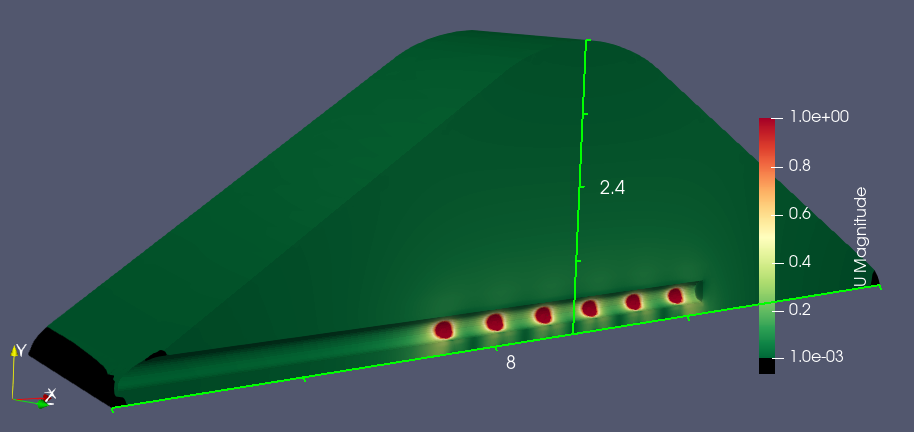

Paper 4: Modelling Sugar Beet Storage Temperature. This was the development of base mechanistic Computational Fluid Dynamic model of a sugar beet clamp.

* this paper is part of the course work component of the project and wasn’t included in the thesis.

SIDE PROJECTS

As with most research, as many questions as answers have popped up along the way. Also, as an industrial doctoral student, I was 20% employed to do other things within the organisation. Here are some of these ‘side projects’.

- modelling sugar beet surface area

- modelling airflow in ventilated sugar beet clamps

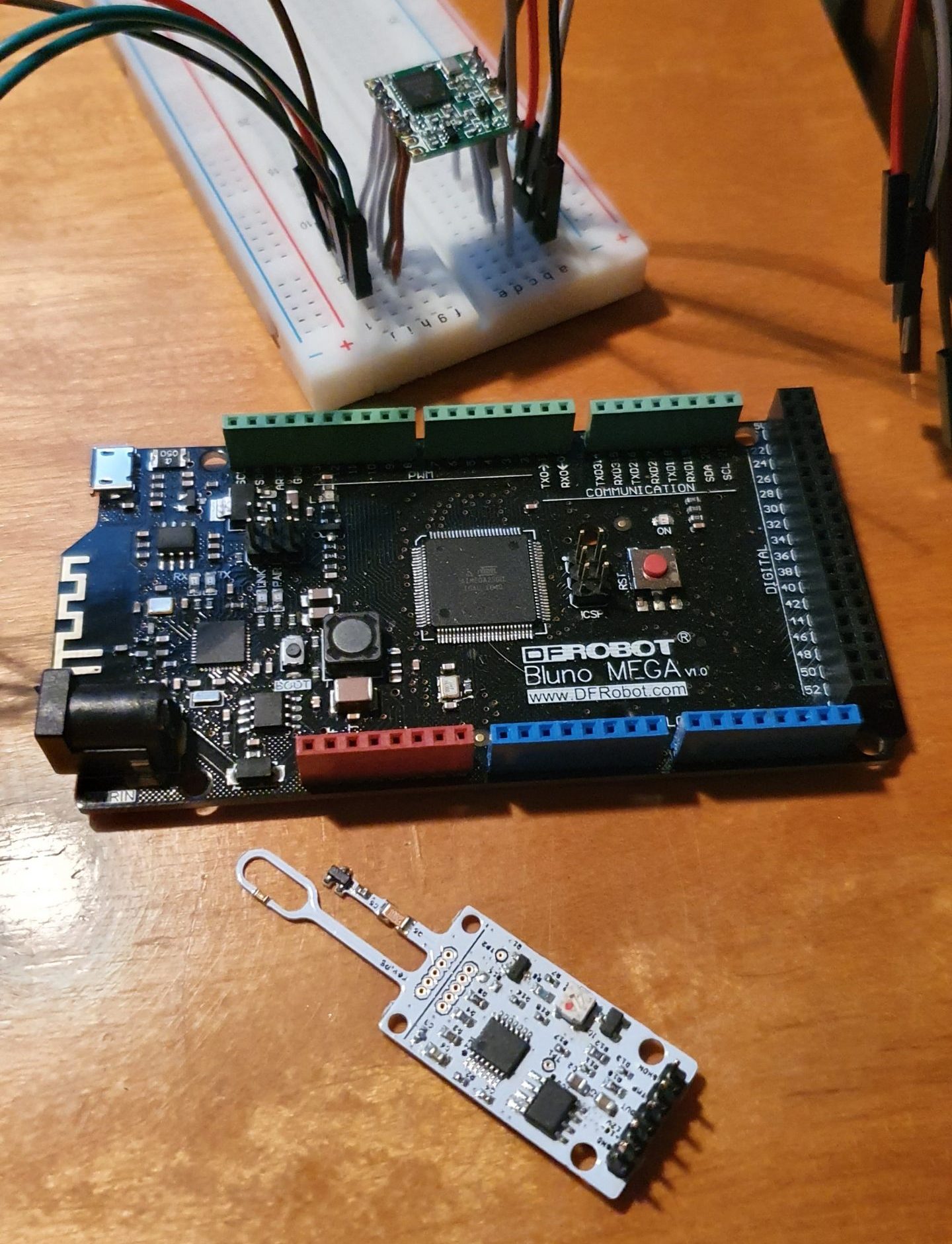

- measuring airflow in sugar beet clamps

- measuring impact pressures on sugar beet

- investigating the importance of water availability at harvest on mechanical properties and damage in sugar beet

- 3D volume measurement of sugar beet clamps

- programming, mainly for data management and presentation

- keeping up to date on relevant progress, like breeding for sugar beet storage

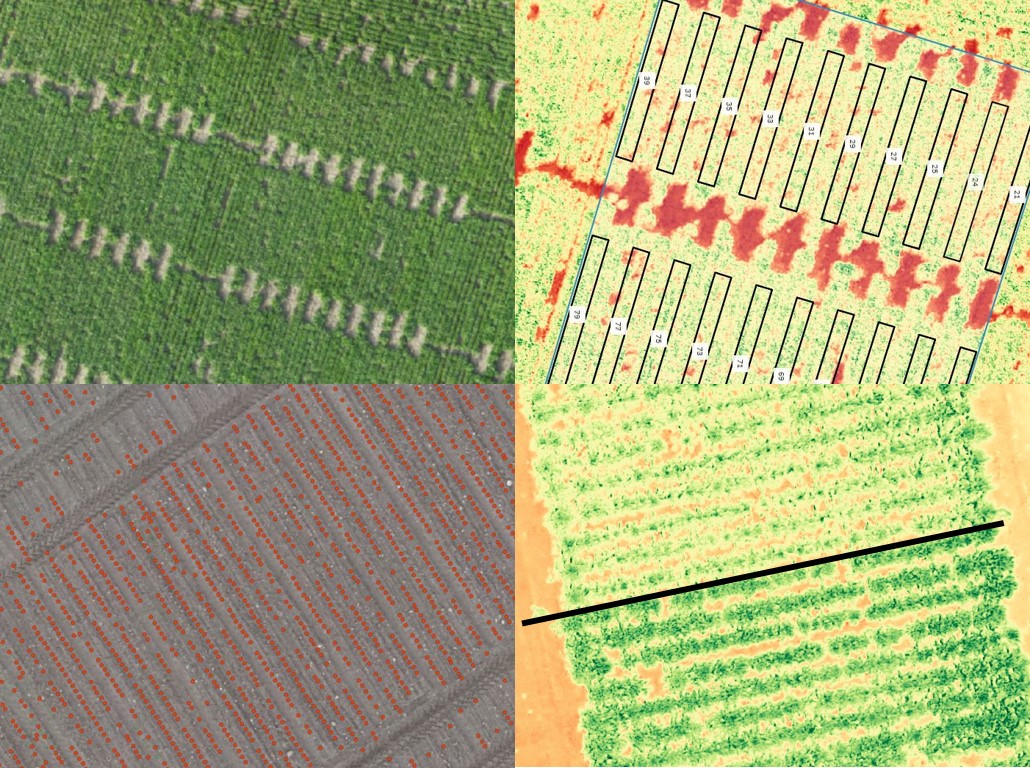

- flying drones and processing the images

- studying the early growth of sugar beet.

MORE INFO

Most information is available on this website, including information on how to get in touch.

There is also this longer overview, as published in Swedish in Betodlarna 2018, nr 3.

LivsID, it’s rationale, partners, and funding.

In Betodlarna 2018 Nr 2 p.40, the new NBR industridoktorand and project was introduced. The LivsID project (livsmedel industridoktorand) resulted from the government’s national livsmedel strategi. The LivsID project sees industridoktorander being co-funded through SLU and their industry actor. NBRs successfully funded project will focus on on-farm post-harvest storage and is due for completion in 2023.

Background, including interest in storage around Europe and Sweden’s comparative advantage.

Deregulation of the European sugar market has sparked renewed vigour in questions related to the post-harvest storage of sugar beets, with many countries seeing in-field storage as an important buffer in managing capacity while national industries adjust to the new conditions. Even prior to deregulation, the investigation of ways to reduce sugar loss in storage were seen as important. For Sweden, our relatively cold climate is both our comparative advantage and our biggest risk. The relatively lower post-harvest temperatures in this part of the world allow us to store for longer in the ideal 4°C + 2 range, but also puts us more at risk of negative frost events.

Focus of this project.

The industridoktorand project is entitled ‘Best practice for long-term field storage of sugar beet under Nordic climate conditions’. The main thrust of the project is to investigate deeper management options that allow the clamp temperature to be maintained within the ideal range, given the Swedish climate.

Components.

The project will run for five years, and include five main components. The first work is will be the most academic; a literature review of sources of temperature in beet storage and the ways in which these can be controlled. The second work will focus specifically on the covering techniques, drawing a lot on the previous work of NBR. Work three looks at how the physical properties and storability of different varieties is impacted by growing season water availability – 2018 should be a particularly interesting year here. These first three works are all under way in 2018. Works four and five will focus on the idea of ‘growing to store’ and beet size, and the economics of in-field storage, respectively.

Work with you the farmer within and beyond the project.

All the field research of this project will be conducted under controlled trial conditions, in the usual way. However, we know that the best research is that which is complemented with observation from on-farm operations. As such, I hope to have the opportunity to sit in the cab with many of you during the length of the 2018 campaign, and those that follow.

WHY THE FINAL TITLE WONT INCLUDE “BEST PRACTICE”.

“Best practice” is an appealing concept. It suggests a solution to the question of how something should be done, based on results of research and experience (Bardach and Patashnik, 2016, Part IV). This appeal means it is also a commonly heard term. But it is not without criticism.

There is ambiguity in the term. To an economist, best practice would result in the economic optimum of a production system. To the technologist, it might lead to the technical maximum. At the same time as there is ambiguity, there is rigidity. Patton (2015, pp190-193) note that a “Best practice” is usually a prescription for how to achieve a given outcome. It lacks context. Even more strongly, Patton (2015, pp190-193) states “Designating something a “best practice” is a marketing ploy…”

The observations against best practice from Bardach and Patashnik (2016) and Patton (2015) are based in the implementation of the idea in policy. Policy usually focuses on the human systems and it could be argued that the complexity and uncertainty is much greater there than that of a sugar beet storage system; one clamp does more or less looks like another.

An expansion of the term may then be “best practice*”, where the asterisk designates “in the given context”, or “when there is insignificant variation in the context”. The economist, however, would recognise that the technology set of each system is likely different. They would also recognise that there are different preferences around, for example, risk and different opportunity costs for labour. At both the individual firm and at a higher level of aggregation, this all means that there are many possible outcomes that could result and that all reach very similar total revenue outcomes – the concept known (somewhat unfortunately in the context of 2022s Internet culture) as “Flat Earth Economics” (Pannell, 2006).

The final, indisputable*, argument against the concept of “Best practice” is that it cannot be “…a scientific conclusion” (Patton, 2015). Science does not work in positive absolutes. Bardach and Patashnik (2016, Part IV) similarly warns “Rarely will you have any confidence that some helpful-looking practice is actually the best among all those that address the same problem or opportunity. The extensive and careful research needed to document a claim of best will almost never have been done.”

* the irony of being so absolute in this sentence is not lost on the author.

The “extensive and careful research” needed to claim “best” has not been done in this instance. Indeed, it cannot be done. This work looks to future scenarios around which there is uncertainty. Then what are the practices this work looks at if not “best”? Bardach and Patashnik (2016) and Patton (2015) both offer alternative terms for what it is the author of a best practice report is likely presenting: Bardach and Patashnik (2016) gives “good” and “smart”, Patton (2015) “better”, “effective”, “promising”.

There is a high degree of confidence that the practices discussed as a result of the research of this doctoral project would fit under any of these banners in different ways. There is confidence that there is causality between the practices and better results, and that there are cost and risk reducing practices. In the end, however, the only term that feels like it would hold up to full scrutiny is simply “practices”. But that is just a little boring…

Patton (2015, pp190-193) distinguishes between best practice and guiding principles. Guiding principles hold when they have been tested in many contexts and situations and still prove effective or correct. With all this in mind, it is the opinion of this author that what we should be pushing is: principles + a full toolbox + context. We the scientists are given permission to work in principles (Patton (2015). We the farmers need tools to make decisions. I the lowly PhD student is trying to summarise the former, and add to the latter.

References

Bardach, E. and Patashnik, E. M. (2016). A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The

eightfold path to more effective problem solving. CQ Press, SAGE, Los Angeles, California,

5th edition.

Pannell, D. J. (2006). Flat earth economics: The far-reaching consequences of flat payoff

functions in economic decision making. Review of Agricultural Economics, 28(4):553-

566.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: integrating theory

and practice. SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, California, fourth edition.